In times of complex challenges like climate crises or loss of biodiversity, there is not only the need for more scientists but also for a more positive attitude and advanced understanding of science by society (Ashbrook, 2020). The lack of scientific understanding is often grounded in school experiences and how science and related subjects are brought to students. Numerus studies have shown that current STEM (Science Technology Engineering Mathematics) educational practices tend not to be overly inclusive and that many students develop an identity “that science is not for them” (Archer, 2010). Intersectional aspects such as gender, migration background, socio-economic conditions in their homes, the science and educational capital of their parents add to the under-representation of diverse groups (e.g. Seebacher et al., 2021; Votruba-Drzal et al., 2016). Thus, there is a need for widened socio-cultural participation and deconstruction of STEM stereotypes. In addition, instead of looking at the phenomenon from the “leaky pipeline” perspective, where certain groups of people drop out, the shift is towards a “hostile obstacle course” placing the focus away from individuals onto systematic barriers at different levels.

Elisabeth Unterfrauner and Claudia Magdalena Fabian from ZSI argue that including the ‘A’ standing ‘arts’ and creative approaches in STEM education and transforming it to STEAM education can have the desired effect: making education more inclusive, increasing scientific understanding, and fostering a positive attitude towards science, and developing skills needed for facing a world with complex challenges.

The EU-funded Road-STEAMer project (https://www.road-steamer.eu/) aims to research current STEAM practices in Europe and how they could be better integrated in school curricula to make it more accessible for young people. In our paper we would like to share the STEAM approach and discuss initial insights into conditions for uptake in the sense of a social innovation in education.

The term “STEAM” is employed within educational contexts to denote a diverse array of pedagogical methodologies integrating science, technology, engineering, arts, and mathematics. While various approaches exist, within the framework of the RoadSTEAMer project, specific elements commonly found in STEAM practices are delineated. These include fostering collaboration among students, educators, and external stakeholders; transcending disciplinary confines; nurturing creativity; promoting critical thinking, active engagement, and practical application; addressing authentic real-world challenges; and upholding principles of inclusivity, personalized learning experiences, learner agency, and equity. The connection between science subjects, arts and, hands-on approaches like maker activities cannot only foster the knowledge transfer of school content, but also support the deeper understanding of the interdisciplinary relationship between different subjects through their application to real-world problem. Maker pedagogical approaches combine several of these elements. Maker pedagogy is an approach emphasising hands-on, experiential learning through creating, designing, and building in collaborative makerspaces. Learners engage in cross-disciplinary projects, fostering creativity, collaboration, and a sense of ownership over their learning. This approach empowers learners to iterate on designs, solve real-world problems, and see the relevance of their creations.

Changing educational practices from STEM to STEAM maker education can be viewed as ‘social innovation in education’ following the definition by the Centre for Social Innovation, ‘Social innovations are new concepts and measures for solving social challenges that are accepted and utilized by social groups affected’ (Centre for Social Innovation, n.d.), with effects ranging from on an individual to societal level.

However, for the approach to become a true social innovation, it must be utilised and practiced by educational institutions.

In the context of a workshop with around 40 stakeholders from schools, members of the two maker projects mAke – African European Maker Innovation Ecosystem (https://makeafricaeu.org/) and DBB The Distributed Design Platform (https://distributeddesign.eu/), researchers, members of makerspaces, pedagogues, and non-profit organisations, the conditions for uptake of STEAM approaches as well as policy recommendations were discussed.

The 2-hour workshop was organised along the consortium meeting of the two maker projects mAkE and DBB and structured in different group and working sessions (5 groups, around 8 people per group). Each group worked on different policy recommendations, guided by a template, which was handed out to each group for further exploration. The template for “policy framing prompts” was created by Distributed Design and structured as follows to guide the discussions within the groups:

(1) What is the policy you would like to change or influence?

(2) Who are the policymakers you would need to convince?

(3) What is the entry point to grab the attention of these policymakers?

(4) What are the winning points to convince this policymaker of your position?

(5) What is the long-term change you would see if policy shifted in your favour?

(6) What would the direct benefit be?

(7) What would the wider benefits be?

(8) What should this policymaker do?

The results of the discussion for each step of the template were noted down on post-its and shared with all participants at the very end of the workshop. One person from each group took over the role of a “speaker” and proposed the elaborated ideas of their group to the other groups.

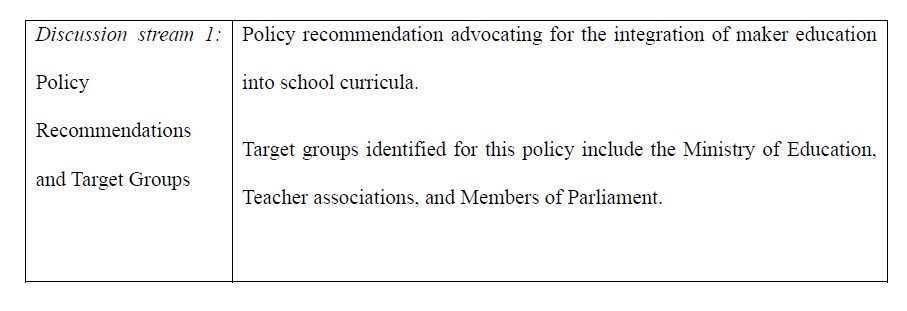

The following table shows the main discussion streams and exemplary points of discussion.